The Brain-Beauty Connection: A Look at Neuroaesthetics

Neuroaesthetics, an innovative new area of neuroscience research, has the potential to help us understand the ways our brain responds to art. The truth is that aesthetic experiences — and the arts — are hard-wired in all of us; they are evolutionary imperatives, encoded in our DNA as an essential part of our humanity. In addition, they are fundamental to our health, well-being, and learning. In this blog, we will explore the brain’s connection to the arts, along with a few prominent initiatives changing the healthcare world through art therapy.

The Power of the Arts

According to evolutionary biologist E.O. Wilson, the arts are reinforced in the brain through reward, pleasure, and fear circuitry, which confirms their link to our survival as a species. As they did in our evolutionary past, the arts still serve the same primal function today: to help us to communicate and connect.

In fact, Dennis Dutton, in his book, The Art Instinct, argues that the drive to make art is encoded in our genes, going all the way back to the DNA of our earliest ancestors.

Anthropologist and author Ellen Dissanayake agrees that art has played an essential role in our evolution and ability to adapt. In 1995, she wrote in her book Homo Aestheticus, that self-expression and the creation of art is a basic human need.

Through her fieldwork, Dissanayake documented this universal artistic impulse in cultures around the world. She found that even those with few material possessions practiced decorating objects, personal adornment, and community song and dance rituals.

From the sacred chanting of Gregorian monks and Native American dance rituals to the present day, the arts have been used as healing tools throughout the ages. However, it’s only over the past 15 years that scientific research has come to the notion that the arts are something humans can’t afford to live without.

Your Brain and the Arts

Aesthetic experiences, and their impact on the mind and body, are much more than the sum of individual brain regions or activities. Sophisticated neural networks are created in your brain to achieve heightened states of connectivity.

One of the core neural mechanisms at play is the process of perception, by which external stimuli enter the brain through the senses and are processed by the brain’s perceptual systems.

Eric Kandel, in his book Reductionism in Art and Brain Science: Bridging the Two Cultures, proposes that the co-mingling of our sensory and cognitive functions dictates perception. Essentially, we take in the world through our senses and make meaning through cognition; this interplay results in an aesthetic experience unique to each specific person.

Neuroaesthetic researchers are also studying the activation of reward systems and the default mode network when viewing or creating art. The reward system releases feel-good brain chemicals, such as dopamine, serotonin, and oxytocin, which trigger sensations of pleasure and positive emotions.

In fact, according to The Telegraph, looking at a painting, sculpture, or other artwork increases blood flow to the brain by as much as 10%, which is the equivalent of looking at someone you love.

Still, viewing art isn’t just about making sense of the shapes. Rather than just thinking art is beautiful, we, as humans, want to place ourselves into the artwork. This placement occurs through a process known as embodied cognition, in which mirror neurons in the brain turn things like action, movement, and energy you see in art into actual emotions you can feel.1

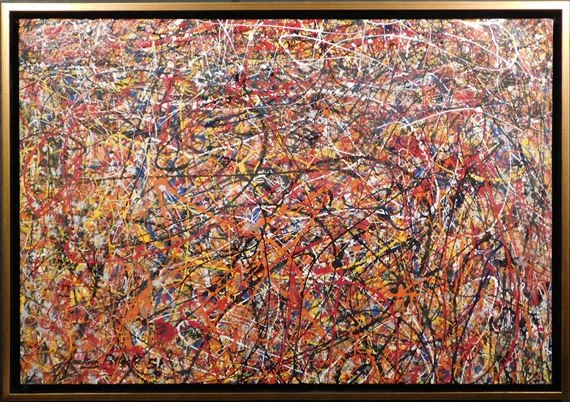

Embodied cognition starts when you look at a piece of art. The more you analyze the piece, the more you place yourself within the scene and can actually feel the quality of the works. For instance, viewers of a drip painting by Jackson Pollock can often feel like they are the ones flinging the paint onto the canvas.

Pictured: Drip painting by Jackson Pollock Source: Forbes

However, creating art invigorates the brain in ways that are distinct from merely viewing art. Studies have credited the actual production of visual art with increases in functional connectivity in the brain along with enhanced activation of the visual cortex.2

Researchers compare the process of creating art with exercise for the brain and even suggest that, similar to how physical exercise aids the body, creating art may help to keep the mind sharp and lucid well into old age.3

A Study on the Connection Between Neurology and Art

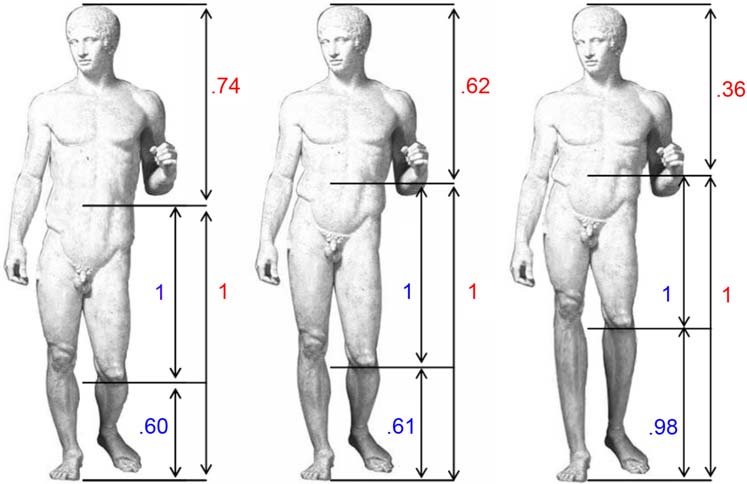

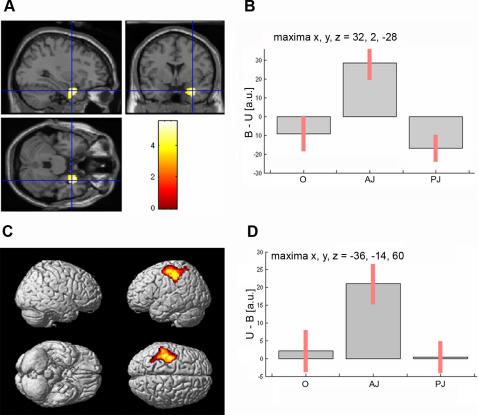

A study carried out in 2007 by a team of neurologists attempted to answer the question of whether beauty is completely subjective or not. To do this, they showed the volunteers images of Classical and Renaissance sculptures while they were in a magnetic resonance machine.4

The participants were shown the original images, then the same sculptures but with modified proportions. After seeing the photos, the volunteers had to say whether they liked them or not, and then make a judgment on the proportions.

Pictured: An example of the modified proportions of a sculpture Source: Research Gate

The scientists found that, upon observing the original sculptures, there was an activation of the insular cortex. This region of the brain deals specifically with abstract thinking, decision making, and perception.

When the participants thought the sculptures were beautiful, the right part of the amygdala showed a response, which is the area of the brain that’s crucial in the processing of emotions like satisfaction and fear.5

Pictured: Brain scans show activity when subjects perceive beauty. Source: Research Gate

The Pioneers of Neuroaesthetics

In the late 1990s, the study of the intersection of brain sciences and the arts was first coined as “neuroaesthetics” by Semir Zeki, a renowned neuroscientist, and professor at the University College of London. The initial research focused on empirical aesthetics by examining the neural bases underlying how we perceive and judge works of art and aesthetic experiences.

At the University of California, San Diego, neuroscientist V.S. Ramachandran developed the “eight laws of artistic experience,” which is based loosely on Buddha’s “eight-fold path” to wisdom and enlightenment. The laws were developed to describe the core neural mechanisms underpinning our enjoyment of visual art.

Ramachandran theorized that tactics employed by visual artists, such as the use of symmetry, balance, and grouping, generate an aesthetic appeal and pleasurable response for which the viewer’s brain is exquisitely wired.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, French neuroscientist Jean-Pierre Changeux studied the role of emotion and memory in the contemplation of art. He theorized that the experience stimulated a complex mental synthesis allowing us to link forms and figures to a larger meaning.

Using fMRI, neuroscientists Ed Vessel from the Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics and Amy Belfi at Missouri University of Science and Technology have added to Changeux’s work by exploring the default mode network’s role in the mental synthesis that ultimately shapes what we find most aesthetically meaningful.

This new wave of research wasn’t just concerned with visual art. In the 1980s, for example, Robert Zatorre, a cognitive neuroscientist at McGill University in Montreal, explored the neurological impacts of music. Zatorre believed that understanding how we experience music on a neurological level could lead to a better understanding of the structure and pathways of the brain as a whole.

“Increasing numbers of investigators are convinced that music can yield valuable information about how the brain works,” Zatorre said in an article published in the journal, Nature. “They believe that the study of the brain and the study of music can be mutually revealing.”

Zatorre’s work proved that making and listening to music engages functions and networks across the brain, including those involved in memory and learning, reward and pleasure, and emotion. In the case of playing music, it connected pathways from the sections of the brain that deal with senses to the sections that deal with motor skills.

Anjan Chatterjee, a neuroscientist at the University of Pennsylvania, further defined the experience of art as a trinity of sensation, emotion, and meaning. He proposed that an aesthetic event triggers an emotional response that can result in a sense of deeper personal significance.

Antonio Damasio, a neurologist studying the neural systems that underlie emotion, decision making, memory, language, and consciousness says, “Joy or sorrow can emerge only after the brain registers physical changes in the body.The brain is constantly receiving signals from the body, registering what is going on inside of us. It then processes the signals in neural maps, which it then compiles in the so-called somatosensory centers. Feelings occur when the maps are read and it becomes apparent that emotional changes have been recorded.”

Neuroaesthetics Continues to Evolve

Today, the field of neuroaesthetics continues to evolve with a growing body of evidence demonstrating the direct impact of the visual arts, architecture, design, digital media, and music on the human brain, biology, and behavior

Cutting-edge brain research is revealing in grand detail how aesthetic experiences enter the brain through the senses and how they profoundly impact our biological circuitry. In fact, scientists can now identify biomarkers that offer measurable ways to characterize changes in the brain.

Now, when people are creating or experiencing some art forms, wearable sensors and mobile devices are being used to measure changes in breathing, temperature, heart rate, and skin responses. These technologies allow us to capture more accurate information as we engage with the world in real time.

However, there are many issues when it comes to health and wellbeing around the world, and unfortunately, these problems are continuing to worsen. For example, neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, as well as mental health disorders such as depression, are straining public health systems.

Neuroaesthetics offers research-based evidence that a variety of arts-based approaches may work to improve quality of life, mobility, mental health, speech, memory, pain, learning, and more. Interventions like these could potentially lower the cost and burden of chronic disease, neurological disorders, and mental health issues for millions of people.

Research-To-Practice Neuroaesthetic Initiatives

A multitude of research-to-practice initiatives have launched around the world, paving the way for a shift from theory to impact. Here’s a deeper look into three prominent neuroaesthetic initiatives:

Creative Forces: NEA Military Healing Arts Network

Pictured: A military member painting Source: Psychology Today

For those in the military, adapting to life at home after the traumas of war can be incredibly difficult. With traumatic brain injuries, post-traumatic stress disorder, and depression on the rise in the military, service members and loved ones may find it hard to understand and address these invisible wounds on their own.

Creative Forces: NEA Military Healing Arts Network is a partnership of the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), the Department of Defense, and the Department of Veterans Affairs. It involves a creative arts approach to help heal service members and veterans dealing with war trauma through writing, music, or art-making, alongside conventional medical treatment.

In a popular TED Talk, Melissa Walker, an art therapist and researcher at the National Intrepid Center of Excellence, explained how making art can help service members access pre-language areas of the brain through the use of symbols. She goes on to mention how mask making practices can enable individuals to unlock traumatic experiences by turning nightmares and painful memories into something that can be shared and released.

Clinically, art therapy has been shown to reduce symptoms such as flashbacks, nightmares, and interrupted sleep, and increase tolerance of hyper-vigilance, pain, and stress. In addition, it can help channel aggressive behavior and anger into healthy forms of self-expression, along with reducing the sense of isolation service members may feel when facing combat trauma.

The Creative Forces fully acknowledges that trauma is not limited to service members; it believes that the discovery of cost-effective arts-based interventions is critical to the overall health and wellbeing of the entire world.

You can learn more about Creative Forces: NEA Military Healing Arts Network here.

Dance for PD

Pictured: Individuals with PD dancing Source: Mark Morris Dance Group

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder affecting an estimated ten million people worldwide. It causes a host of movement-related symptoms, including tremors, muscle rigidity, slowness, and postural instability. Patients often describe challenges with everyday tasks that require fine motor control, such as writing and buttoning clothing.

As the disease progresses, patients may develop a slow, shuffling gait and experience balance problems. As their mobility decreases, patients may lose their autonomy and self-confidence and suffer cognitive and mood problems, all of which severely impact their overall quality of life.

Programs like Dance for PD are designed to combat both physical and mental sides of the disorder through creativity, social interaction, and “voluntary” movement, cued by music to activate specific brain regions.

In 2001, Olie Westheimer, the founder and executive director of the Brooklyn Parkinson Group, approached the internationally-acclaimed Mark Morris Dance Group proposing the idea of a rigorous, creative dance class for her members.

Westheimer knew from her own dance background that professional dancers developed cognitive strategies to execute difficult movements with power and grace and wanted to bestow some of that wisdom upon people with PD.

What started as monthly classes for about six people in Brooklyn has evolved into Dance for PD classes in more than 250 communities in 25 countries around the world. The program’s teaching practice is underpinned by evidence from 38 peer-reviewed studies indicating its possible benefits.

Through Parkinson’s Quality of Life measurements, class participants with Parkinson’s disease reported physical, emotional, and social benefits. In addition, early research shows improvements in motor and cognitive function as well as mood.

You can learn more about Dance for PD here.

Playful Learning Landscapes

Pictured: A child playing a Playful Learning Landscapes instrument Source: Dunham Foundation

In the United States, children from under-resourced communities enter formal schooling well behind the starting line. It’s been proven that they commonly fall behind their peers in language development, reading readiness, and spatial skills.

While education is known as the great equalizer in closing developmental gaps, the reality is that children only spend 20% of their waking hours in school. The Playful Learning Landscapes initiative is bringing together scientists, urban planners, architects, and educators with the goal of utilizing the other 80% of children’s time through creative placemaking, which is a practice that infuses arts and culture into community spaces to effect social change.

In the Supermarket Speak Project, for example, colorful and engaging signs are posted throughout stores in low income neighborhoods to encourage caregiver-child interactions that center on skills like counting and learning the names of various foods. Pilot research showed a 33% increase in caregiver-child communication.

Pictured: Supermarket Speak Project signs Source: Playful Learning Landscapes

In The Power of Play: A Pediatric Role in Enhancing Development in Young Children, published in the journal of The American Academy of Pediatrics, individuals associated with Playful Learning Landscapes touched on the critical importance of play in the development of a child’s executive function and social skills.

“Play is not frivolous: it enhances brain structure and function and promotes executive function (ie, the process of learning, rather than the content), which allow us to pursue goals and ignore distractions.”

The authors go on to say that “An increasing societal focus on academic readiness (promulgated by the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001) has led to a focus on structured activities that are designed to promote academic results as early as preschool, with a corresponding decrease in playful learning.”

Playful Learning Landscapes’ mission is to reverse this trend through a variety of branching initiatives, projects, and research. It’s now collaborating with organizations, communities, and cities around the world to create more playful and enriching learning environments for children and families.

You can learn more about Playful Learning Landscapes here.

In Conclusion

The power of the arts has always been with us, but a deeper understanding of its impact on the brain is relatively new. Research is proving that experiencing or creating art sparks a dynamic interplay among brain cells that spearheads billions of changes affecting our thoughts, emotions, and actions, which in turn can promote healing and empowerment. Its potential benefits transcend class, gender, age, race, and culture, making the arts a superpower for all.

What are your thoughts on how our brains connect with the arts? Let us know in the comments!

References:

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/embodied-cognition/ [1]

https://www.nature.com/articles/srep39185 [2]

https://kids.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frym.2017.00019 [3]

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/5817749_The_Golden_Beauty_Brain_Response_to_Classical_and_Renaissance_Sculptures [4][5]