All About Psychedelics

Psychedelics, also known as hallucinogens, are a group of substances that are commonly used to change and enhance sensory perceptions, thought processes, and energy levels, and to facilitate spiritual experiences. They include chemicals, such as LSD, and plants, such as peyote. The use of psychedelics goes back centuries in many cultures with some still being used today in religious ceremonies to experience spiritual or heightened states of awareness. In this blog, we’ll dive into what psychedelics are, how they work on the brain, and why the page is turning on using psychedelics for medical conditions such as depression and anxiety.

Types of Psychedelics

While psychedelics are loosely described under a general rubric, there are big differences between them. The following are some of the most commonly used psychedelic substances:

Acid (LSD)

Pictured: Acid and LSD sheets Source: FRANK

Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) is a chemically synthesized hallucinogen, developed from ergot, a kind of mold that grows on the rye grain. Also known simply as acid, LSD was widely used in the 1960s until it was made illegal in 1968.1 The use of LSD has continued, despite being a controlled substance, although its use has gone through phases of greater or lesser popularity.

Dimethyltryptamine (DMT)

Pictured: DMT Source: Elephantos

N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT) is a simple and potent psychedelic molecule found in many plants, such as psychotria viridis (chacruna) and diplopterys cabrerana (chaliponga), as well as animals. While DMT is naturally produced in the human brain, researchers are still working to understand the purpose of the molecule.

DMT can cause intense perceptual, cognitive, and emotional changes.2 However, the effects of DMT are much shorter than those of other psychedelics, typically lasting only an hour. This has led to DMT trips being referred to as the “businessman’s trip” or “businessman’s lunch.”

Ayahuasca

Pictured: Ayahuasca Source: The Guardian

Ayahuasca is a brew of two plants, one of which contains DMT, while the ayahuasca vine contains harmala alkaloids or monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). Therefore, ayahuasca may be chemically reduced to DMT + MAOIs taken by mouth, while DMT is typically used via inhalation without MAOIs.3

Indigenous people in countries like Colombia and Peru have been using ayahuasca for hundreds of years as medicine and for religious worship. Compared to the intense and short-lived experience of pure DMT, an ayahuasca trip lasts for a few hours.

Many Westerners seeking psychedelic medicine travel to countries such as Brazil or Peru where ayahuasca is legally available. In this setting, ritual experiences are often embedded within a longer retreat. For example, the tea is often consumed on multiple nights with healing and integration work done during the day.

Ketamine

Pictured: Ketamine Source: Drug Target Review

Ketamine is a well-known medication that was originally used as an anesthetic during minor surgical procedures. Over time, ketamine has grown in popularity recreationally due to its sedative and muscle-relaxing properties. Ketamine is a dissociative substance, which means it acts on different chemicals in the brain to produce visual and auditory distortion and a detachment from reality.

Mescaline

Pictured: Peyote Source: NZ Drug Foundation

Mescaline is a naturally occurring psychedelic substance found in certain species of cactus, the most well-known being the peyote cactus. The effects of mescaline, which are similar to those of LSD, were well documented in the classic text on hallucinogens, The Door of Perception by Aldous Huxley.

Although peyote is a Schedule I drug and is therefore illegal, the listing of peyote as a controlled substance does not apply to the use of peyote in bona fide religious ceremonies of the Native American Church. Any person who manufactures peyote for or distributes peyote to the Native American Church, however, is required to obtain registration annually and to comply with all other requirements of law.4

Ololiuqui

Pictured: Ololiuqui seeds Source: Magic Mushrooms Shop

Ololiuqui is a naturally occurring psychedelic that is found in the seeds of the morning glory flower, which grows in Central and South America. Like mescaline, ololiuqui has a long history of use in spiritual rituals among indigenous groups where the plant grows but unlike mescaline, it’s not a controlled substance in the U.S. leading some to consider it a free “herbal high.”

Psilocybin

Pictured: Magic mushrooms Source: Healthline

Magic mushrooms contain a naturally occurring type of hallucinogen called psilocybin, which is found in certain fungi. There is a wide variety of hallucinogenic mushrooms, and their legal status is somewhat ambiguous, as they can be found growing wild in many parts of the world.

Their natural origins can make them appealing to young people, keen to experiment with these “free drugs.” But mushrooms carry particularly high risks given the toxicity of some varieties, which can even be lethal.5

MDMA

Pictured: MDMA Source: La Hacienda Treatment Center

MDMA, also referred to as ecstasy or molly, is more difficult to categorize as a psychedelic as the hallucinogenic effects are less pronounced, and the mood-enhancing and stimulant effects are more noticeable to the user than some other psychedelics. However, it can induce hallucinations and delusions.

It’s possible to have a bad trip on ecstasy, although this is not as common as bad trips on LSD or mushrooms. Ecstasy has also been associated with increased risks of health problems arising from overheating, dehydration, and water intoxication.6

How Psychedelics Work On the Brain

Psychedelics, such as LSD and psilocybin, are chemically similar to the neurotransmitter serotonin produced by the brain. Serotonin is involved in many neural functions including mood and perception. By mimicking this chemical’s effects, the substances exert their profound effects on subjective experience.

DMT too acts via serotonergic pathways, but also through other routes – for instance, DMT binds with sigma-1 receptors that are involved in the communication between neurons.7 Meanwhile, ketamine – among many other effects – blocks NMDA receptors that are involved in the functioning of the neurotransmitter glutamate.8

A key brain area for the effects of psychedelic substances appears to be the temporal lobe, the location of much of the emotional and memory functioning. For instance, removal of the front part of the temporal lobe as a radical treatment for epilepsy has been shown to prevent the psychological effects of taking LSD.9

Interestingly, abnormal activity in the temporal lobe, such as during seizures, can lead to events similar to near-death experiences. An effect shared by different psychedelic substances is that they increase the amount of disorganized activity across the brain – a state that neuroscientists describe as being “higher in entropy.”10

A consequence of this is a reduction in the activation of a group of brain structures known collectively as the “default mode network,” which is associated with self-conscious and self-focused thought. One theory, then, is that psychedelics provoke a spiritual state of oneness with the world by increasing the brain’s entropy and suppressing the ego-sustaining activity of the default mode network.11

Psychedelics For Medical Conditions

Psychedelics were used in psychotherapy in the 1960s, but this was halted for mainly political reasons until quite recently. Psychological research has since revived the use of psychedelics in experimental psychological treatment.

However, regulated treatments are currently experimental and not accessible to many people. While the research on psychedelic medicine for mental illness is still considered new and emerging, some studies have shown compelling results:

Psilocybin

A 2021 study in the Journal of Psychopharmacology found that high-dose psilocybin improved symptoms and quality of life when given with psychological support. After six months, about 80% of participants continued to show clinically significant decreases in anxiety and depressed mood.12

Another 2021 study in the New England Journal of Medicine showed that patients with moderate to severe major depressive disorder who received two doses of psilocybin did just as well — if not better — at six weeks than patients who received daily doses of escitalopram, which is an antidepressant medication.13

Psilocybin may also be an effective addition to current treatments for quitting smoking, according to a pilot study.14

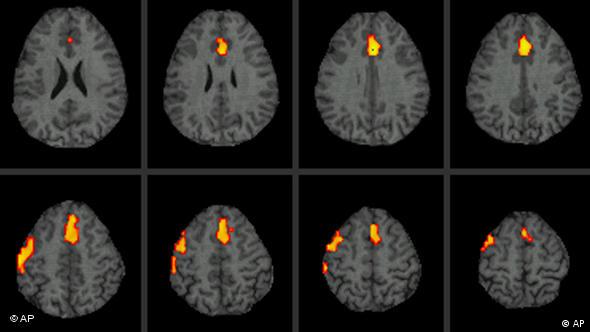

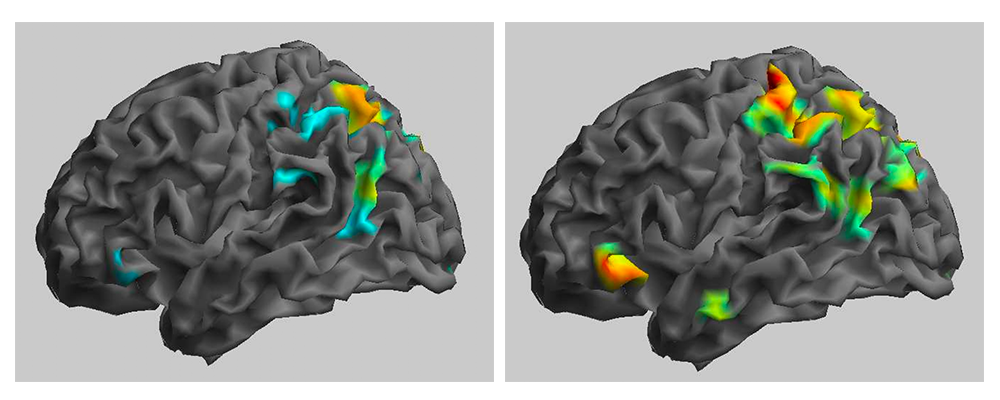

Pictured: An fMRI of patients undergoing psilocybin treatment for depression with their brain regions appearing to be more interconnected than before the treatment Source: DW

LSD

LSD-assisted psychotherapy — meaning a combined intervention of therapy and medication — may lessen feelings of anxiety among people with life-threatening illnesses who are anxious about their illnesses, according to a small study with 12 participants. Follow-up research with participants one year after treatment found that those decreases in anxiety had lasted.15

A review of six clinical trials with 536 participants linked a single dose of LSD administered within treatment programs for alcohol use disorder to a decrease in alcohol misuse.16

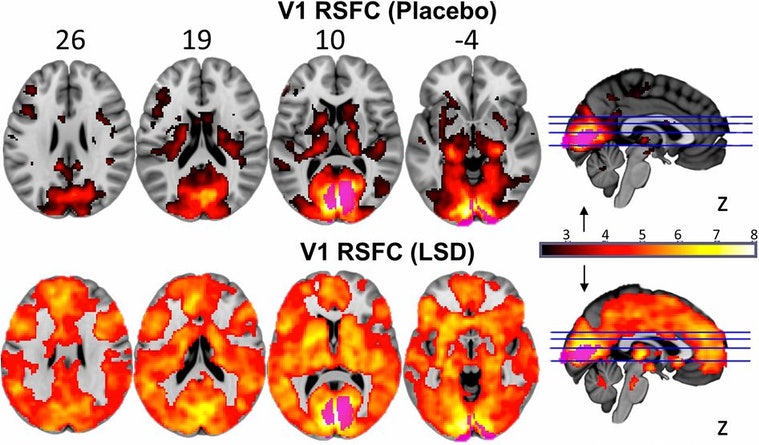

Pictured: The brain on LSD shows higher resting-state functional connectivity between the visual cortex and the rest of the brain Source: Inverse

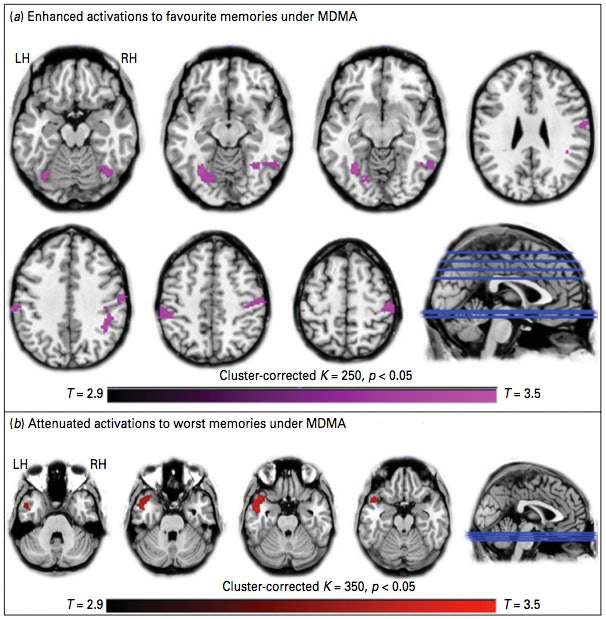

MDMA

Some of the most compelling results for MDMA as a treatment for mental illness have come from clinical trials involving people with PTSD. In a study with 90 participants, investigators found that 67% of people treated with MDMA-assisted therapy no longer met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD 18 weeks after starting treatment.

The authors of the study concluded that “MDMA-assisted therapy represents a potential breakthrough treatment that merits expedited clinical evaluation.”17

Pictured: MDMA amps up the good feelings of happy memories and dulls the pain of bad ones as shown in brain scans Source: Inverse

Ketamine and Esketamine

Intranasal esketamine, also known as-ketamine or S-ketamine, is the S enantiomer of ketamine. Administered together with standard antidepressant treatment, it was found to significantly reduce depressive symptoms and suicidal thoughts among patients with depression and high suicide risk, a small 2018 study found.18, 19

And in a March 2022 study, researchers found that among 537 people who received intravenous ketamine therapy in a clinical setting between 2016 and 2020, more than half of the patients experienced an improvement in their symptoms, and nearly 30% achieved remission.20

Pictured: Ketamine appears to strengthen connections between neural networks in people with severe depression. In a study comparing neural activity prior to a ketamine infusion (left) and six to nine hours after an infusion (right), a single dose made the brain more responsive to a simple sensory stimulus, the light stroking of a finger. Source: Brain Facts

A Nod to Ram Dass

Pictured: Ram Dass Source: GQ

Ram Dass was born Richard Alpert on April 6, 1931, to a successful Jewish family in Newton, Massachusetts. Though he was Bar Mitzvahed and grew up in a traditional house, he considered himself an atheist. “I didn’t have one whiff of God until I took psychedelics,” he said.

On March 5, 1961, Alpert had his first psychedelic experience with psilocybin. As the layers of his identity melted away, he went into a panic. The young professor was now able to see a wider vision of his place in the universe.

Interested in exploring consciousness, this expansive experience ignited his curiosity and would color his brief but memorable tenure at Harvard. Realizing the enormous potential of psychedelics, Alpert and Timothy Leary, a fellow Harvard professor, launched the Harvard Psilocybin Project in 1960.

Experiments ranged from scientifically rigorous to personal use and exploration. The Concord Prison Experiment (1961-1963) is an example of a more academically sound study and helped set the stage for psychedelic clinical trials today.

Another famous experiment, the 1962 Good Friday Experiment, was the first controlled double-blind study of psychedelics. The goal was to assess whether ingesting psilocybin could induce a mystical experience in the religiously predisposed.

Ten divinity students were given psilocybin, and ten took a placebo. The results were immediately clear. “It was absurd,” Alpert said, “because, in a short time, it was obvious who had taken the psilocybin. . . . They would stagger out of the chapel and say, ‘I see God! I see God!’”21

In 1963, Alpert was formally dismissed from Harvard. Along with Leary and other colleagues, he moved to the Millbrook Estate in New York where they continued to experiment with psychedelics. Their goal was to uncover a permanent path to higher consciousness.

During his four-year stay at Millbrook, he maintained professional relationships with those in the medical, psychiatric, and academic fields. He co-authored a number of books, including The Psychedelic Experience with Ralph Metzner.

After traveling to India and spending eight months with the guru, Neem Karoli Baba, at a temple in the Himalayas, the newly-named Ram Dass returned to America. In an effort to reach more people, he started many foundations, the most famous of which is the Living/Dying Project.

To Ram Dass, conscious living includes conscious dying. This is a major theme in today’s renaissance of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. Compassionate use of psychedelics for terminal patients focuses on accepting one’s own mortality and living each day to the fullest.

He was involved in countless other foundations and movements, all aimed at improving people’s spiritual wellbeing. Ram Dass passed peacefully on December 22, 2019, and his powerful legacy continues to shape the world of psychedelic medicine.

To learn more about Ram Dass, click here.

Which Psychedelics Are FDA-Approved for Use?

Currently, Spravato (esketamine) is FDA-approved for treatment-resistant depression. It’s administered as a nasal spray by a health professional.22 Though esketamine is a psychedelic medicine, its prescribing information lists hallucinogenic experiences as a side effect rather than a mechanism of action, or how the substance works.

“With the typical way esketamine is used, folks are told to ignore the psychedelic effects as a side effect, which is the opposite of true psychedelic therapy where one is encouraged to pay attention to the altered state of consciousness and try to learn from it,” says Matthew W. Johnson, Ph.D., a professor of psychedelics and consciousness research in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore.23

Some doctors prescribe ketamine — which is FDA-approved as a general anesthetic — “off-label” for depression. This means it’s not yet FDA-approved for depression, but some health professionals deem the medication appropriate for certain patients. Some physicians provide ketamine for depression at specialized clinics throughout the United States.24

Additionally, the FDA has granted breakthrough therapy designations to psilocybin for depression and MDMA for PTSD. This designation accelerates their pathway to FDA approval.25 But these medicines aren’t legally available to the public yet and can only be used as part of a clinical trial.26

In Conclusion

Considering the most recent scientific and clinical developments in understanding the actions of psychedelics, a statement made in 1980 by Dr. Stanislav Grof seems particularly relevant today:

“It does not seem to be an exaggeration to say that psychedelics, used responsibly and with proper caution, would be for psychiatry what the microscope is for biology and medicine or the telescope is for astronomy. These tools make it possible to study important processes that under normal circumstances are not available for direct observation.”

Although studies are showing positive results, there are still many unknowns, such as the ways these drugs will be administered if they become FDA-approved. However, the popularity surge in psychedelics research will likely continue gaining steam.

What are your thoughts on psychedelics being used medicinally? Let us know in the comments!

—

References:

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/306889 [2]

https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/ayahuasca [3]

https://www.britannica.com/plant/Lophophora-williamsii [4]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psilocybin_mushroom [5]

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5008716/ [6]

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5148235/ [8]

http://9.g00gleweb.com/heiwu.php [9]

https://www.payam.com/s/Psychedelic-Assisted-Psychotherapy-for-Trauma-and-Chronic-Pain.pdf [10]

https://www.payam.com/s/Psychedelic-Assisted-Psychotherapy-for-Trauma-and-Chronic-Pain.pdf [11]

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5367557/ [12]

https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa2032994 [13]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25213996/ [14]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24594678/ [15]

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0269881112439253 [16]

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-021-01336-3 [17]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29656663/ [18]

https://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17060647 [19]

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165032721014142?via%3Dihub [20]

https://news.tufts.edu/magazine/fall2006/features/ultimate-trip.html [21]

https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/from-street-drug-to-depression-therapy [24]

https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20191122005452/en/FDA-grants-Breakthrough-Therapy-Designation-Usona-Institutes [25]